Published in Counter-Currents, March 31, 2021

Remembering Robert Brasillach (March 31, 1909 – February 6, 1945)

Here we have a continuation of the narrative presented in past installments, describing Brasillach’s auto-tour through wartime Spain in July 1938, accompanied by his brother-in-law Maurice Bardèche and their friend Pierre Cousteau. As before, I have translated it directly from Brasillach’s memoir Notre avant-guerre (1938-41).

In the last section Robert Brasillach gave a quick summary of his automobile tour, along with his impressions of the Nationalist spirit and sense of social justice in the new, revolutionary Spain. Here he fleshes things out with a more thorough description of Toledo, where the Spanish Civil War really began, with the siege of the Alcázar (July-September 1936).

After Toledo the Frenchmen move on to Madrid’s University City, where some of the fiercest fighting of the war had taken place. In fact it was still taking place in mid-1938, when Brasillach, Berdache, and Cousteau visited. There was little more than a stone’s throw between the trench lines of the Nationalists and those of the Red “International Brigades.” At one point our jolly threesome, apres-dejeuner, fortified with excellent food and wine, go exploring the local trenches. Like college kids, they slip their official escorts and nearly get themselves blown up by the Reds or arrested as spies by the Nationalist side!

The Robert Brasillach we have as narrator here is not quite the pious and socially concerned fellow we saw last time. This Brasillach is a darkly funny guy, with a love of the absurd. He takes us to a crazy woman who complains to the mayor of Toledo that her husband and son have been killed . . . but mostly she’s upset because she hasn’t got any potatoes. And she rustles her empty canvas sack to make the point!

Brasillach meets a pastry cook who prides himself on being the Famous Frenchman Who Lived Through the Alcázar Siege . . . although the Keystone Kops explanation of how the pastry cook escaped execution by the Reds might not be entirely reliable.

And then we’ve got some Moorish soldiers on the Nationalist side, most of whom have little Spanish and less French. They encounter Brasillach and friends in the trenches outside Madrid and suspect them of being Red spies.

This episode of Brasillach, Cousteau and Bardeche—three somewhat nerdy French journos taking an after-lunch stroll near a no-man’s-land where they shouldn’t be at all—would make a really nice little film script. Except, of course, Brasillach was executed by the Reds in 1945, and I don’t believe a script of this particular scope has ever been green-lighted for production.

Robert Brasillach himself was a film and literary critic, not a travel writer, and this comes through in passages where he drops place names and personages, and makes a joke without offering some substantive or intriguing detail. There’s one funny anecdote that takes place just before our three Frenchmen get lost in the trenches. While they’re touring the remains of University City, the local Nationalist brass invite them to an impromptu “sumptuous lunch” at the Architecture building—one of the few local structures that haven’t been bombed to smithereens. Brasillach tells us they were treated to this lunch because these officers hope these French journalists will write it up and turn University City into a great gastronomic destination! This might well be banter on the soldiers’ part, with Brasillach playing along, suggesting he’s going to do a “Michelin three-star”review of the lunch.

Then he jokes to us, in an aside, that the only trouble with this fine-dining locale is that it’s nearly impossible to get to, seeing as you’re fifty meters from the enemy lines, with bombs exploding and mitrailleuses blasting away, right outside the window.

But ironically, after all this discussion of matters gastronomique, Brasillach leaves out the central detail of what they ate for lunch! As I say . . . he was not a travel writer!

From Notre avant-guerre

. . . .After Burgos, where we enjoyed those unforgettable scenes of lively and joyous crowds promenading down the [Paseo del] Espolon at 8 p.m. every evening, we moved on through dusty Valladolid, full of soldiers at rest. And then we finally reached Toledo.

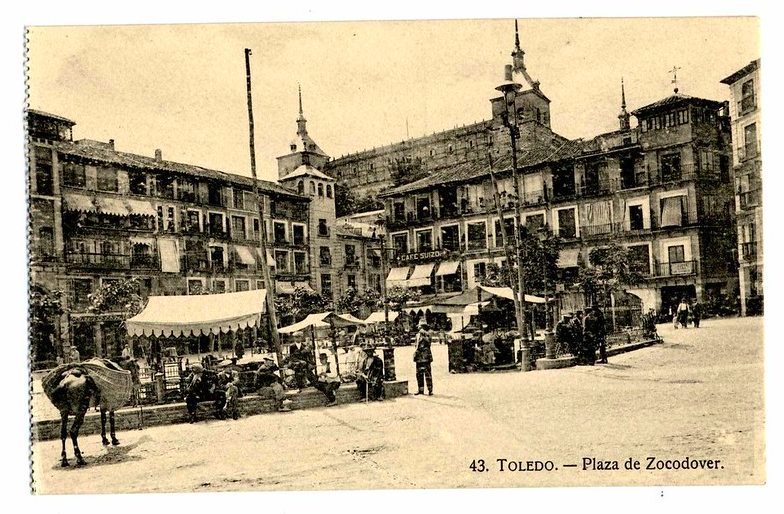

Barely two kilometers from the enemy lines, Toledo is even deader than when Philippe Barrès saw her. [French politician and journalist Barrés, 1896-1975, had written of Toledo in Le Matin.] It’s a strange town, buried in the night. In those winding little Arab streets, there’s no light other than flashing blue lamps. Off in the Plaza de Zocodover, cafés are braced by sandbags, stacked up all the way past the ground floor; and moreover, these cafés are closed at midnight.

The streets are deserted, the shops are dismal. You can sense the menacing war, the nearby front, even if this marvelous green and yellow neighborhood itself hasn’t been smashed to pieces yet. The rest of Toledo hasn’t suffered too much, at least, but Zocodover Plaza is in ruins. It hasn’t entirely disappeared from the face of the earth, that is true; we can dream of restoring it as a monument, and we can tell ourselves that San-Juan-los-Reyes (St. John of the Monarchs), in front of the Alcázar, might quickly heal these wounds. What we can’t imagine is how we could restore this weird masterpiece, with those fifty irregular balconies; these houses that lack style, but are somehow exquisite, with their crazy, marvelous facades.

Zocodover Plaza

Cannons and the mines have forever destroyed this unique success of Spain. So close to the front, Toledo has not yet resumed its former life.

A little after this we met the mayor at a café. Don Fernando Aguirre had lived through all seventy-two days of the siege of the Alcázar. [July-September 1936]. He told us about it with a kind of puckish glee

“I didn’t like boiled horse at all,” he confessed. “Not at all. Maybe if there had been salt… But no salt! So I ate some flour. It was not very good, because of the sawdust. But it was better than the boiled horse!”

And he laughed very loudly, in his gastronomic chagrin.

Of the Alcázar itself, of the exterior nothing remains at all, apart from monumental ruins. We toured the underground passages, with their enormous walls. We saw the entrance from which they aimed a single little cannon. And then there was the flour mill they made out of a motorcycle engine, and the telephone from which Colonel Moscardó heard his son’s voice. [1] And the bakery . . . and all the other small mementoes of the siege: the last bottles of medicine, the bread, the remaining supply of grain . . .

They’d set up an infirmary in the chapel, and covered it with a large red carpet. They set up a copy of the Virgin of the Alcázar (the original statue of which is now in the cathedral). Here we saw the small room where was born one of the two children of the siege, named Ramon-Alcázar, and over there we saw the swimming pool where still slept about twenty of their dead . . . and beside that, there were the bathhouses where bodies were buried standing up. Standing out in the courtyard, his armor pierced with a bullet, was the statue of [Holy Roman Emperor] Charles V.

Every step we took, we encountered the presence of war. When we went to the town hall, a little old woman clutching a waxed-canvas tote-bag approached Señor Alcade, the mayor. She talked quickly while crying, and occasionally opened her canvas bag. They killed her husband, her son—she said—and now she has no potatoes!

But who were they? The Reds? Whites? We never found out. She babbled on in terror and confusion, slapping her bag with desperation. In tears she repeated her three interchangeable sorrows—her dead son, her dead husband, and no potatoes; and then she’d focus her despairing, mad chatter to her mysterious waxed-canvas bag.

We knew there was a Frenchman in the Alcázar, but didn’t know much about him. Turns out his name was Isidore Clamagiraud. He was a pastry chef in Zocodover Plaza. He had a little rat face, with freckles, and he told us boldly, with a smirk: “C’est moi! Yes! I am the famous Frenchman of the Alcázar! “

At the end of July and beginning of August [1936] Isidore had gone out, twenty evenings in a row, looking for flour. Then, on the twenty-first night, he got caught! Next morning, the Reds were about to shoot him.

But that very day, the French consul in Madrid was making a tour of Toledo to ensure the repatriation of French nationals. He heard that Isidore was going to be executed. So he waited for a funeral cortege to come down the street, on its way to the Synagogue del Transito [originally a 14th century Sephardic synagogue, later used as a Catholic church and museum]. And then he jumped on the condemned man, pushed him into his car, and drove off at high speed—in the best style of American cinema!

Isidore the pastry chef recounted all this to us quietly, as though it were the most natural thing in the world.

In the streets of Toledo, we’d come across some legionaries from the Madrid front, resting up for a couple of days sometimes. One of them, a Frenchman who fought in the last war, and who had been fighting in Spain since the beginning, told us some beautiful yet horrible stories.

“The Reds tried to take over Toledo in 1936,” he said. “We sent the Legion against the tanks. Do you know the best way to deal with the tanks? We throw a gasoline bottle, it breaks, we throw a grenade, and the tank ignites like a match. Only problem was, when we got to the tanks, the bottles were full of water! Our little Red friends had played a nice trick on us. When we got back we were one hundred out of seven hundred.”

He shrugged his shoulders: such are the misfortunes of war.

We asked him what the legion’s general opinion was, regarding the Frenchmen in their ranks.

“In my bandera“, he told us, “the commandant gave an order: any legionnaire who speaks ill of France will have two days in a peleton. Do you know what the peleton is? We get up at four o’clock, we work non-stop, we go to bed at two in the morning. And if we have to deal with a really bad head-case, we put the bag on him: a bag on his back, very heavy, that he can never take off, even to sleep. So what the commandant says, goes.”

He told us stories, and was probably making up a lot of them. But one of them was the true gen: “You remember the mobile guard captain Monsieur ——, killed by the communists in Colombes, this was three or four years ago? He had a son, sixteen at the start of the Revolution. One fine day, the kid leaves for high school with his books in his bookstrap. Only this time he had borrowed some money from his sister. Three days later he’s in the legion. We have to believe that it was his intention to fight against those who killed his father. So now, he’s eighteen, he’s been wounded five times, everyone loves him. He doesn’t drink, he doesn’t think of women. This lad is one shining example. We were together at the Cité Universitaire. [2] When he had a little money, he’d go down to Toledo and buy himself a kilo of caramels. He’s just a kid.”

In the future, Toledo will undoubtedly reclaim its former destiny as a sumptuous place, a city of enchantment. Maybe the Alcázar will be rebuilt. Maybe not. We can only hope that a wisely directed public policy, like the social movements of the Falange, will revive life in these city streets and desolate countryside. Today, Toledo may be nothing more than the museum of warring Spain, but it is the most moving and the most magnificent of museums. Civic life might well resume elsewhere while Toledo remains wounded, torn, left with ruins and memories: a fate bestowed on no other city of Spain. Neither Burgos nor Seville nor Segovia, however seductive they are, suffered such a martyrdom.

For months to come, with its veiled lights and abandoned streets, Toledo would remain the very city of death.

As for the University City of Madrid, it is no further from the capital than the Cité Universitaire de Paris is from ours.[3] It was in Madrid itself, at the gates of the city, that Franco’s soldiers took refuge for a long time, in a sort of gateway besieged on all sides, constantly undermined and only able to communicate with the back-country through some wooded area and a pasarela (footbridge). They’ve occupied and fortified this region across the bridge. It’s where they lived, and where they sorted out strategy.

When we were at the border and we said we wanted to go to the University City, they knew exactly what we meant: “Ah! Ah! la pasarela!… “

Señor Merry de Val [4] repeated this to us, as did our Spanish press official. Apparently we were to go get travel certification in a small, dry, brown village. This turned out to be San-Martin de Valdeiglesias, I believe. A place we had trouble searching out in the Spanish desert.

The lieutenant-colonel then mentioned the pasarela again, and added, with a laugh: “Pequeno riesgo!” A little risky!

Up to this point we assumed that this «pasarela» was some kind of boat for foreign journalists. Now we were told that we had to cross a footbridge “under the fire of a machine gun”—one-by-one.

In the morning, Pierre Cousteau was singing, to the tune of The Legion (A legionnaire knows how to die …):

Oh, a journalist faces death . . .

And in fact it was so: we went one-by-one, but the machine gun never shot at individuals.

Nevertheless, when we got to the end of this famous footbridge, we found a stretcher left out to receive the wounded . . . with a bouquet of flowers. It all looked pretty macabre.

We were much less impressed, I must say, by these last ten meters of footbridge than by the course we’d just completed, some five or six times longer, concealed by some very scant shrubbery, while bullets like swarms of bees were hitting the trees around us. As I write about this eighteen months later, this all seems like an ironic introduction to the new adventure we’d taken ourselves into. For us and our comrades there would be other footbridges, and other shrubbery to cross and hide behind, when we were no longer mere tourists. But our pasarela tragica experience will keep a privileged place in our memories.

Once we crossed that famous footbridge, we came across an encampment that might well have passed for a holiday camp. The lieutenant-colonel had a little pink house amongst the trees: this was the “Villa Isabelita”, which was recently built for him, with kitchen, bathroom, all modern conveniences.

As for the soldiers, they’d built themselves a swimming pool, a pretty good-sized one from what I could tell, where they could happily forget the sun and the scorching heat. Soon enough, we visited a tabor de regolares (Moroccan colonial troops), banging away on a piano sheltered by leaves. To tell the truth, we quite forgot that the enemy lines were less than a hundred meters away.

We almost forgot all those kilometers we traveled under the sun, through the trenches of the University City. But from time to time, we’d still hear that little whistle, or a dull, dry noise that we novices still couldn’t distinguish as bullets that might miss us or hit us.

They were curious, those trenches, extraordinarily clean, and paved in the strangest way in the world. From the little palaces around University City, the most varied and sometimes luxurious materials were borrowed. Marble, mosaic, rough brick alternated in beguiling eclecticism. But mainly, their trench architects were into radiators. Yes, they would lay their radiators on the ground to let the water flow, thereby avoiding the wooden slats which were generally used in trenches. It was even possible to walk through the trenches and—from behind a large stone in the loophole, and often as close as 25 meters—see the trench-lines of the Reds, and the high townhouses of Madrid so very close; as well as the giant Telefonica building, and the churches.

Within the University City proper, few buildings—or ruins, I should say—belonged to the Nationalists. The colonel of the sector, who usually had charge of us and accompanied us everywhere, would point them out to us with his cane:

“Here is the Philosophy Department… It is Red.”

“Naturellement!”

“Here is Medicine, Dentistry … also Red! But the hospital-clinic is ours. And also the Architecture department … And the Casa Velasquez.”

We saw the destroyed Plazete, which was the “folly” of the Duchess of Alba; we visited the remains of the Casa Velasquez, the maison for French language and culture here; and then we took in the most extraordinary ruination suffered by the enormous hospital-clinic. This had been one of the most beautiful in Europe, but now it was completely ransacked, with dozens of floors collapsed and folded on top of each other like paper.

The Architecture department was in better condition. It was there that the local officers immediately invited us to the most sumptuous lunch—as they believed that we would be listing University City as one of the top gastronomic destinations for tourism in new Spain. (A destination that right now is . . . unfortunately . . . a little difficult to reach!)

While there, we also visited some rooms of non-commissioned officers and soldiers (on the wall, holy pictures only). All the while we were shielded by armored window-shutters and the occasional blasts of machine guns. And then in the most sheltered corner of the Architecture department, we found the University City Hospital. This was perhaps the miracle of Spain. They’d set up a whole ward there for advanced surgical services. The wounded were transported there immediately and treated at once. All the while, the enemy was fifty meters away. Constant shooting, constant bombing. Not very far from here a mine exploded one day, taking out thirty Moroccans at once.

Everywhere, moreover, mines were ready to explode. Trenches were evacuated and left under the watch of a single sentry who waited for something to go off. And it was under these conditions that a modern surgical hospital had been set up and operated un-transportable wounded. “Here is one,” the surgeon told us. “Wounded three days ago, in the lung and in the liver. Today, he has temperature of 37.5º, so he’s safe. If it had been necessary to move him anywhere, he would have died. We’ll evacuate him at night, by the footbridge.”

At the bend of a passage, Pierre Cousteau and I lost Maurice, while our guides continued to advance. Finally we found ourselves in a line of unknown trenches, deserted. It was time to start shooting again, bullets whistling overhead. Presently some Moorish troops appeared, and watched us civilians with curiosity.

We tried to talk to them. They didn’t know Spanish. We were a bit uneasy. We realized what an odd sight we were. Here we were—French, in University City, Madrid, very close to the International Brigades (a mere thirty meters away from our trenches at some points). Not a good look for us, is it? An unlikely bunch.

But then a Moroccan approached us when he heard us speak. “Toi Français?” he said. He was from the French zone of Morocco, and he was glad to see us. He led us to an officer who would eventually take us back to Villa Isabelita.

By now our guides had become very worried, and they were interrogating Maurice. Calling him “Don Manuel” [the mis-written name on his transit pass], they thought he was just ignoring their questions in Spanish. Little communication here, but they felt reassured when they heard the French words “tuer”, “fusiller”, “Mores” [Moors]—easily recognizable to them.

So it seems that we escaped it all beautifully. Our press official who was responsible for us gave sighs of relief when we finally turned up.

To cries of “¡Arriba Francia!” we left and went back to Toledo, then moved on to quieter places. We drove all day to reach Zaragoza where the Grand Quartier is located. It was a very amusing city, and we would not find another one so lively; just as we’ll never see Burgos so vastly swollen with ministries and troops, as it was when we saw it in wartime. We were left at the Grand Hotel, which is a caravanserai where we three were offered a small room with camp beds . . .

* * *

We saw the Struggle for Nationalism in a Spain at war. But there was also a Nationalism Triumphant that we could visit—even if it was a nationalism of a somewhat different essence. I mean, of course, Germany.

About Germany, we were always curious. Our two peoples are the products of history, as well as geography. (Maybe more geography than history?) And there was a lot to see in Germany, if you had the time to spend there. A lot of us felt that we needed to cover Germany quickly, because maybe we wouldn’t really have that much time to see that country at peace.

Anyway, in 1937 we made up our minds go to the Congress of Nuremberg. We were pretty sure we’d find some newspapers happy to have some slightly biased special correspondents, and that this would enable us to cover part of our travel expenses. Annie Jamet [5] joined a trade mission from Lyon, which was going to attend the Congress, accompanied by a few curious parliamentarians, including M. Pomatret, now Minister of Labor.

One happy motorist invited by Je suis partout, Pierre Cousteau, took his wife, as well as Georges and Germaine Blond (Georges was covering the Congress for la Liberté). I didn’t join these folks till the last few days. [6] [Brasillach footnote: Georges Blond’s account was published as A Hundred Hours with Hitler in l’Revue Universelle.]

We had a lot of fun. We motored the route from Nuremberg to Bamberg (where we were lodged, as there was a lack of space in the holy city!), while singing the “Madelon,” always under the respectful eye of the Bavarians, and I think we made a charming impression. We got to talk with a number of Germans who were involved with Cahiers franco-allemands journals with Fritz Bran and Otto Abetz, whom we knew somewhat. We had wide scope to take in the new Germany.

A hundred hours is roughly the time I spent in Germany, and I have to ask myself how I avoided being biased by all the contradictory impressions. For one thing, it’s a bit pretentious to judge a country after such a brief exposure. Neither Germany nor Hitler are simple things. We can read a few books and meet a few Germans, and think we feel at ease there, and imagine (even if we’ve never even been there!) that we know what we like and don’t like about the place.

But the reality is quite different. The fun gets mixed together a very different way from anything we anticipated. Our hundred hours has surprises and contrasts, things you might not notice if you’ve been living there for years. I mean, look at those Bavarian villages that you go through on the train and automobile. There they are in the middle of your green and pleasant journey, childlike decorations along the way.

Whether the roofs are pointed or round, you still have those brown, visible beams, and the flowers in all the windows . . . and that’s the Germany that’s dear to romantics (including Jean Giraudoux [7] who gave us these impressions in the first place). Perfectly shaped, as graceful as a Nuremberg toy! It’s medieval, it’s feudal, it dresses up the roads with a contrast that might well astonish you.

So, along the little paved streets of Nuremberg and Bamberg, along rivers and canals, near cathedrals and impressive statues . . . you see the old Germany of the Holy Roman Empire, now merged into the Third Reich. Nothing really surprising here, though . . . apart from these millions of flags hanging from the facades. No posters here, as you’d see in Italy. Just the flags, though some immense, hanging there, five storeys up, others less extensively, but still maybe three per window! Can we imagine such an adornment, so joyful under this gray sky, which is associated with the touching baroque of the sculptures, the old houses and the flowers on the balconies?

Here is a people who love flowers. We see it in the garages, where the workers devotedly furnish their clients’ motorcars each morning. This is the sort of thing that has always attracted nostalgic devotees of the “good” Germany, people like the fat Madame de Staël [8]. But let’s not let love of flowers distract us from the harder realities.

Quite literally, there was not a village which was not proud on this triumphal road to Nuremberg, during this week from September 6 to 13, where the National Socialist Party was holding its convention in the old town of Franconia, the holy week of the Reichsparteitag. This lavish decoration merely pointed us to the ceremonies we’d come to see, and prepared for the sacred rites of The New Germany. Big banners, here and there, welcomed us. At the gates of cities, we spotted others asking us to come next year. No other announcements except those which were seen at the entrances to villages and a few inns where it was simply stated, with restrained politeness: “Jews are not wanted here.” But outside the venues devoted to the celebrations of the new culture, you wouldn’t see anything other than flowers and flags. If we wanted to know more, we would need to investigate beyond this façade of grace and freshness.

We went to Exhibitions. In Nuremberg there was a great Anti-Marxist show going on, with photographs and posters of Marxist crimes around the world. The sailors of the Deutschland, the ship bombarded by the Spanish Reds, received special honors, naturally enough. The French figure prominently among the revolutionary nations, because of Jean-Jacques [9]; but to please our own amour-propre, the race theorists have made a plea to Voltaire and Napoleon, whose anti-Semitic phrases they display in big letters. The exhibition was well done. We French contributed the remains of a bus that was bombed on 6 February 1934, as an example of «Rouge» barbarism. [10] Our French folk would pass this display and smile.

Notes

[1] The reference is to one of the most dramatic—and perhaps characteristically Spanish—episodes of the war in Spain. Soon after the Alcázar siege began in July 1936, the Republicans (aka “Reds,” or “Loyalists”) captured the son of the Alcázar’s commandant. By telephone they ordered Colonel Moscardó to surrender, or else they’d shoot the son, Luis. Luis came to the phone, and his father told him to commend his soul to God. Luis was shot, and the siege held out for two months, long enough for Francisco Franco’s troops to reach the Alcázar and defeat the enemy. [2] Meaning they were in the trenches by University City outside of Madrid; not attending classes together at university! [3] As close as the University of Paris? The claim looked dubious to me, but in fact Madrid’s University City is only about 2km from central Madrid . . . about as far as the Sorbonne and Latin Quarter is from present-day central Paris. [4] Alfonso, Marquis Merry del Val, 1864-1943, London-born Ambassador of Spain to the United Kingdom, 1913-1931; later, unofficial representative of General Franco in Great Britain, 1936-38. [5] Annie Jamet was organizer of the Cercle Rive Gauche, holding salons and conferences for the young French Right intellectuals on the Left Bank. A close friend of Brasillach’s she accompanied him to Nuremberg in 1937 but died the following year. During the War her husband Henri Jamet ran the Librairie Rive Gauche (bookstore) in the Latin Quarter, at 47 Blvd St-Michel, corner of Pl de la Sorbonne. Les Collabos, articles from L’Histoire (Paris: Fayard/Pluriel, 2011). [6] Georges Blond, 1906-1989, was a contributor to Je suis partout and became renowned after the war with his Histoire de la Légion étrangère (1981). [7] Presumably refers to Giradoux’s play Siegfried (1928). [8] Germaine de Staël-Holstein was the daughter of Louis XVI’s finance minister, Necker, and a would-be romantic groupie of the young Napoleon Bonaparte. In France, Mme. De Staël became a byword for any loquacious, unattractive bluestocking. Brasillach is no fan, as we can see. [9] Must refer to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who is imagined by some to have prefigured the French Revolution. [10] This could be another instance of Brasillach irony. The date is generally associated with Rightist rioting in Paris after the Stavisky Affair (q.v.).