Birch Watchers

Birch Watchers

Margot Metroland

Matthew Dallek

Birchers:

How the John Birch Society Radicalized the American Right

New York: Basic Books, 2023

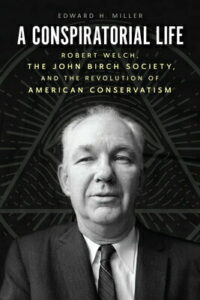

A couple of months back I reviewed a biography of Robert Welch (A Conspiratorial Life) that I regarded as superficial and facile. [1] The author, Edward H. Miller, seemed to have no real feel for the issues that motivated Welch and his followers in the late 1950s and early 60s. In fact Miller displayed little sense of that time at all, as a political era I mean. His notions about Welch and the John Birch Society were funneled entirely through simplistic and disparaging journalism, from that era to the present. These were stories that pushed the idea that Welch was “a conspiracy nut,” and that the Birchers were a semi-secret, far-Right activist group that was somehow akin to the KKK though less overtly racist. The Birchers, Miller decided, were much like the recent QAnon people of a few years back, with their wild conspiratorial imaginings, or the PizzaGate nuts, or those “J6” insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol in early 2021. Or, better yet, Donald Trump himself, with his endless, irresponsible accusations about Mexican rapists and stolen elections. Miller presumably made all these comparisons to entice potential readers who didn’t know any better.

A very different book is Birchers. Maybe because he’s the son of biographer/historian Robert Dallek, Matthew Dallek knows how to keep the reader’s attention by serving up interesting facts instead of flyblown opinions and slogans. On the whole this book is marvelous stuff, an entertaining read and almost free of egregious errors. Dallek occasionally stumbles with silly political cant—he calls Charles Lindbergh the “antisemitic aviator” (ooh that Charlie Lindbergh!) — and/or mistaken identity (he refers to Medford Evans’s journal, The Citizen, as “the white supremacist newspaper Citizen’s Council“). [2] And at book’s end he tries lamely to establish a continuity between early-60s Bircherism and the popularity of Donald Trump. This strained thesis was probably tacked on here because Dallek’s editor thought it made the book more relevant to the Modern Reader. Dallek doesn’t beat this dead horse the way Miller did in A Conspiratorial Life, but the Trump comparison still looks obtrusive and facile, the publishing equivalent of clickbait.

Thankfully, for the most part Dallek rides an even keel, treating all comers fairly if whimsically. He’s appreciative and even enthusiastic when discussing the Bircher activity, at least in the early 60s. In Dallek’s telling the JBS crowd of that early 60s were an energetic and aware bunch of activists, ready and willing to infiltrate local school boards, chambers of commerce, political campaigns, and local media outlets. They did this with skill and imagination. I was doing my laundry when I got to this part in the book. I suddenly stood up and wanted to cheer, right there in my apartment building’s basement laundry room. Because the Birch Society was the sort of outfit you’d want to join back in the early 60s, if you were a young adult. Or even an older one!—one of those “little old ladies in tennis shoes,” as the saying went, describing the Birchers’ invaluable army of dedicated volunteers. Author Dallek is obliged to take an adversarial stance, but you can tell he really admires, even likes these people. They had gumption, they had daring, and mainly, they knew what they wanted.

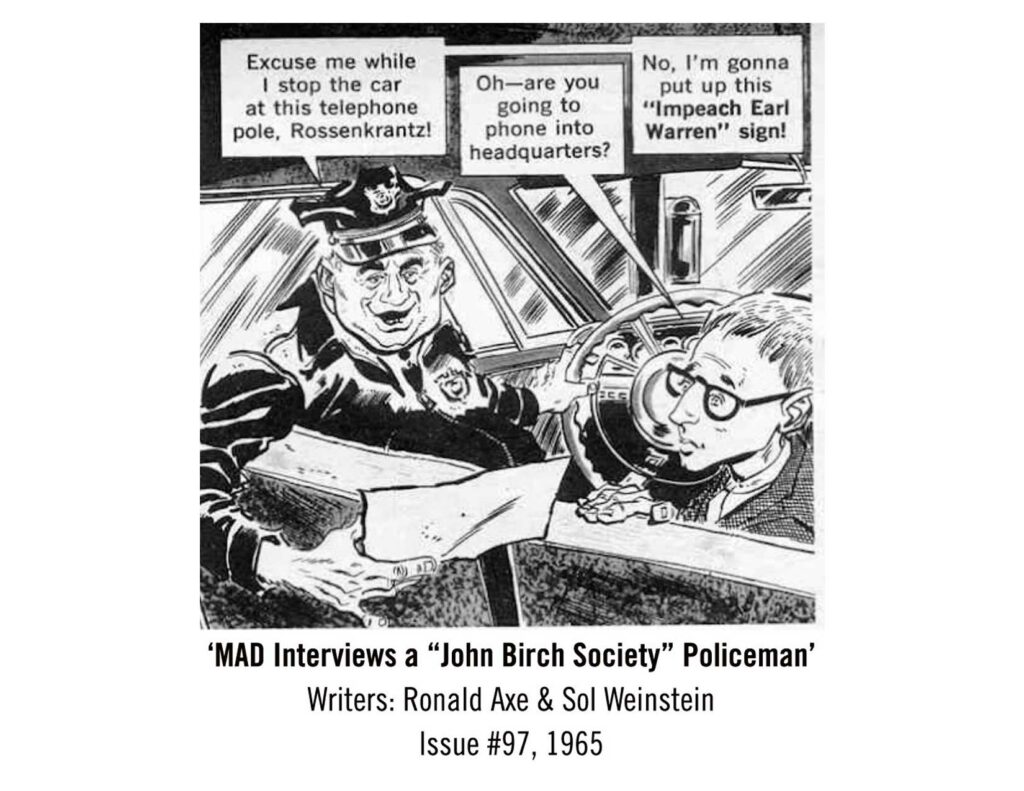

And the story gets much more interesting, because these infiltrating Birchers themselves got well and thoroughly penetrated by anti-Birch spies and provocateurs, notably the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith (ADL). It was like a “Spy vs. Spy” cartoon in Mad: white-hat spy infiltrates the city council and the local Republican party organization; meanwhile black-hat spy slips into the white-hat group to find what’s going on, and maybe sabotage it. The spies don’t necessarily accomplish much, but they do have fun!

The ADL’s campaign against the John Birch Society is an old tale, first recounted back in 1964 in a book by the ADL’s own Arnold Forster and Benjamin Epstein, Danger on the Right [3] which inspired a similarly titled television documentary broadcast just prior to the Presidential election. What Birchers does is fill us in on the backroom information: that is, the practical details of the ADL’s spy operations against the JBS. According to Dallek, during the 1960s and 70s, ran a dedicated espionage program literally called “Birch Watchers.”

Dallek briefly chides the ADL for its deceitful, illegal activities, but cheerfully goes along with their “end justifies the means” rationalization:

Why did a venerable organization devoted to civil rights and civil liberties deploy subterfuge tactics that seemingly contradicted some of its core values? In 1952 the ADL’s general counsel Arnold Forster, and national director, Benjamin Epstein, hinted at an answer to this question. The ADL, they wrote, felt a duty to expose “a vast enterprise” of hate and to disrupt the “works of professional hatemongers” operating in the United States. Meier Steinbrink, the national chairman, spoke of the need for “ammunition for the war to make our land a more perfect democracy.” To the ADL these righteous ends justified the morally questionable means, which included outright spying. As the Birch Society emerged and gained strength, it became an ADL bête noire… By shining a bright, intense light on the far right’s dark side, through whatever means, the ADL hoped to stroke a blow for tolerance, progress, and democracy. (pp. 137-138)

And so on so forth, including the obligatory nod to the “Holocaust”—an anachronistic nod, inasmuch as the term would not acquire its current popular meaning until the 1980s. Read this in a Frontline narrator voice and try not to smile:

Inaction and silence in the face of fascism had enabled the Holocaust and brought dictatorship close to American shores. To the watchers, Birch criticisms of the civil rights movement as a communist plot and of the US foreign policy establishment as the pawns of international elites evoked Hitler’s scapegoating and persecution of Jews and racial minorities. (p. 137)

Wow just wow. Close to American shores! The Duke and Duchess of Windsor in Nassau, you mean? The Dallek tongue surely was well within the Dallek cheek when he tapped out those lines. Or might you think he possibly wrote this unironically? Well, just after telling us that “the ADL went to great lengths to keep its spy program secret” (no, seriously?), he describes the Birch Watchers as “a motley crew bound together by a shared faith in the goal of making America a safe haven for Jewry and racial progress.”

In Dallek’s eyes the Bircher/Birch Watcher face-off was a pretty balanced match. Plenty of skullduggery and silliness on both sides, with no real advantage to either. Again, it’s “Spy vs. Spy.”

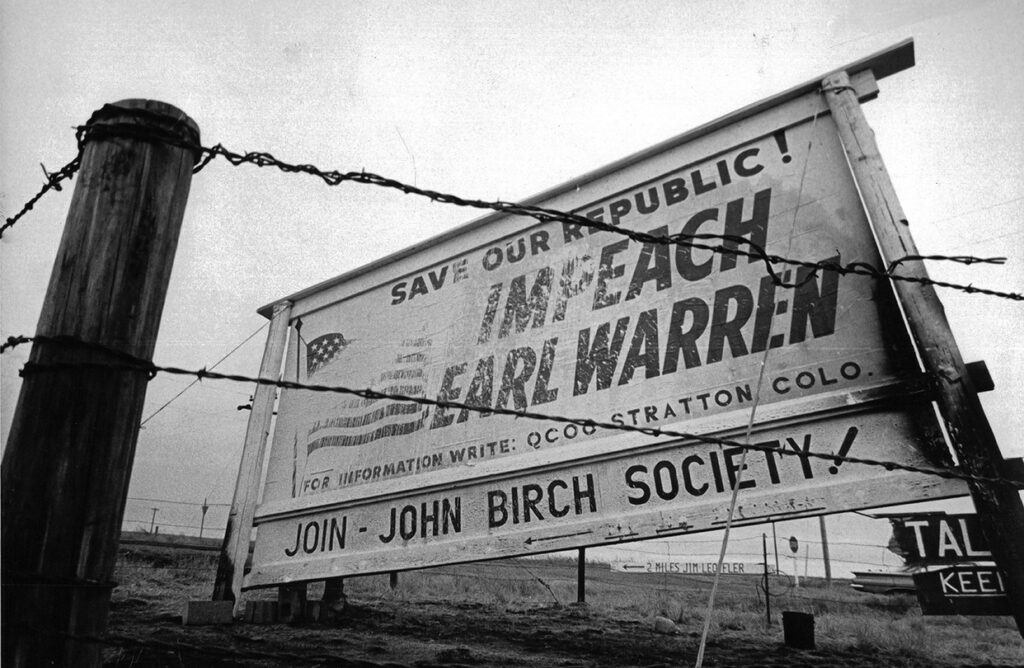

A most intriguing revelation comes at the beginning of Dallek’s “Birch Watchers” chapter, when an unnamed ADL spy (code name: Bos #4) goes to Belmont, Massachusetts and knocks on the door of the two-story, red-brick Birch headquarters. He’s met by none other than Mr. Welch himself, to whom the spy ingratiates himself by claiming to be head of a chapter in New Jersey, on his way back home and hoping to pick up some extra literature. In the course of amiable chitchat in the office, the fake Bircher from New Jersey asks why Westbrook Pegler hasn’t been appearing in American Opinion magazine lately. It turns out that it’s not because Pegler was going off on the Jews, as he sometimes did, it’s because he would write stuff about Chief Justice Warren, and say, e.g., he “wishes that Warren would break both his legs.” Welch wanted to “soften Pegler’s violent-sounding screed” (Dallek writes), but Pegler wouldn’t let him. Furthermore Welch “was furious that he still had to pay Pegler for his unprintable work.”

This report on Pegler must have been disappointing to the ADL home office. They wanted to report that Westbrook Pegler’s “antisemitism” was too much even for the John Birch Society, but actually the fight was about Earl Warren. Veteran columnist Pegler had recently been canned by his newspaper syndicate (Hearst’s King Features), leaving the Birch Society as his one remaining outlet. The ADL’s Forster and Epstein were so fascinated by the Pegler saga that they devoted much of their Robert Welch chapter in their Danger on the Right book to Pegler’s authorial tantrums and public outbursts, This includes the memorable if unpublicized occasion when Stork Club proprietor Sherman Billingsley ejected him from the nightclub, supposedly for carrying on a drunken tirade against David Ben-Gurion. “Peg” then sat down on the sidewalk. When showbiz columnist Leonard Lyons emerged with some friends, Pegler called him a “Jew-Communist” and “kike son-of-a-bitch.” Then Pegler shouted “nigger bastard” at Negro chauffeur who tried to help him to his feet. This is all supposed to have happened on Thanksgiving Day 1962.

This story comes entirely from the ADL, mind you, and you may judge for yourself how true any of it might be. Regardless, it’s a wonderful example of the ADL fixation upon Westbrook Pegler. As you might have gathered by this point, Dallek had access to a lot of ADL memoranda. This makes his endnotes very interesting, as compelling as the text. [4]

You may remember that back in 2008 Vice-Presidential candidate Sarah Palin used an unattributed Pegler quote in her acceptance speech (“We grow good people in our small towns…”). An obscure quotation from a long-dead, unnamed newspaper columnist, and yet it was enough to send up a signal flare and get the opinion media raving for a week.

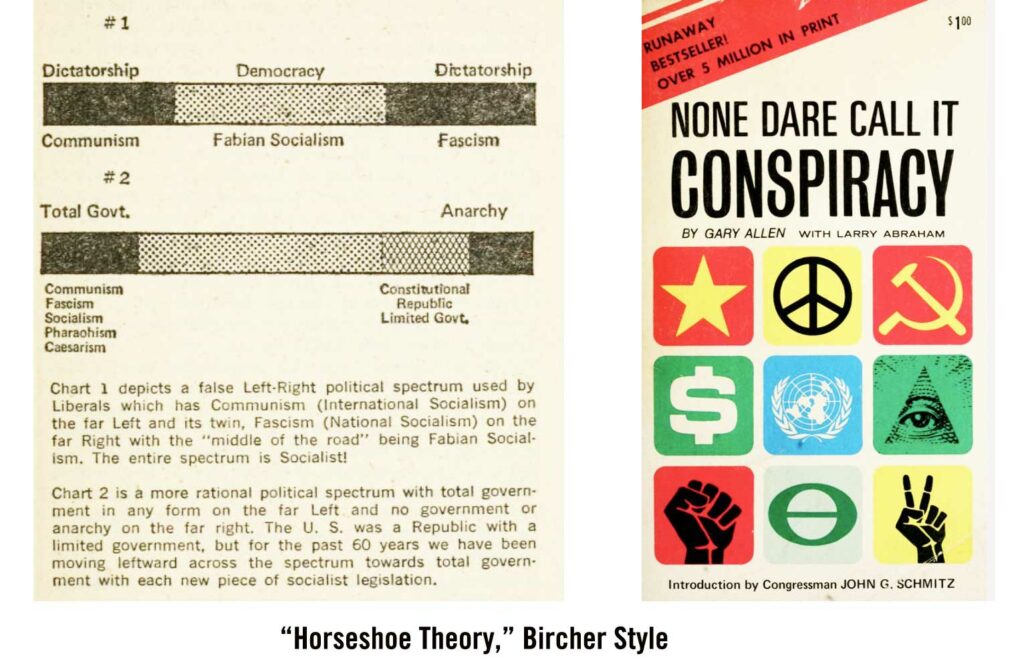

A notable thing about the ADL smear jobs against Rightists and Birchers is that they would compulsively claim that any book or pamphlet of a grandly conspiratorial nature was a “rehash of the discredited Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.” Dallek has them saying this of Condé McGinley’s Common Sense newspaper in 1964, while Forster and Epstein’s Danger on the Right (published the same year) characterizes William Guy Carr’s Pawns in the Game the same way. I noted in my review of the Welch biography, A Conspiratorial Life, the ADL said much the same thing in 1972, post-election about Gary Allen’s None Dare Call It Conspiracy. The assertions are untrue. But from a propaganda angle that does not really matter, because the key point is that the writings are being dismissed as loonytoons “conspiracy” stuff, which is all pretty much the same.

Notes

[1] I completely missed Morris van de Camp’s 2022 in-depth review of A Conspiratorial Life, which treats author Miller rather more respectfully. [2] But I want to cite a substantive error that comes near the beginning, in the summary Introduction, because it’s just a dumb mistake that cannot be blamed on bias or typographical error. Dallek claims thatThroughout the 1950s [William F.] Buckley published writers whose work also appeared in American Mercury, which had become an antisemitic magazine with ties to the Birch Society.

This was a clear impossibility. Buckley did not publish National Review “throughout the 1950s,” in fact he did not begin publication until the end of 1955. And then he declared a ban on Mercury-byline writers beginning about March 1959. (The Mercury had sent out a subscription flyer which, according to the ADL, associated Judaism with Communism and Zionism. Prior to this the Mercury had not be openly accused of “antisemitism.”) Finally, the John Birch Society wasn’t founded till the end of 1958, so any association with NR or AM couldn’t really have begun before then.

It may of course be arguable that nearly every conservative or Right-wing periodical from about 1959 to 1964 had some sort of tie, friendly or formal, to the JBS. This includes National Review, which published Revilo P. Oliver’s book reviews throughout this period. Prof. Oliver had been with NR since its founding, and did not break with the JBS until 1966.

[3] Arnold Forster and Benjamin R. Epstein, Danger on the Right. New York: Random House, 1964. Still a delightful read fifty years on, and not nearly as rantingly paranoid as its title suggests. Besides a long and entertaining chapter on Robert Welch and the John Birch Society, the book’s other attractions include dissections of such other examples of “the Extreme Right phenomenon” as National Review and William Buckley; Human Events; and Young Americans for Freedom. [4] An indication of the ADL’s, or at least Arnold Forster’s, obsession, comes out in correspondence between Forster and head spy Isidore Zack. “Any chance of our getting our hands on the typescript copy of that [Westbrook Pegler] article? I would love to see its anti-Semitism. We may need such evidence in the near future.” (February 3, 1964.) Alas, there was no damaging typescript to be had. Instead, for the John Birch Society chapter in Danger on the Right, Forster had to fill out his Westbrook Pegler attack with a description of a February 1964 Pegler appearance in Los Angeles, in which Pegler defended the use of the words “kikes” and “sheenies” and made fun of the lynching of Leo Frank.

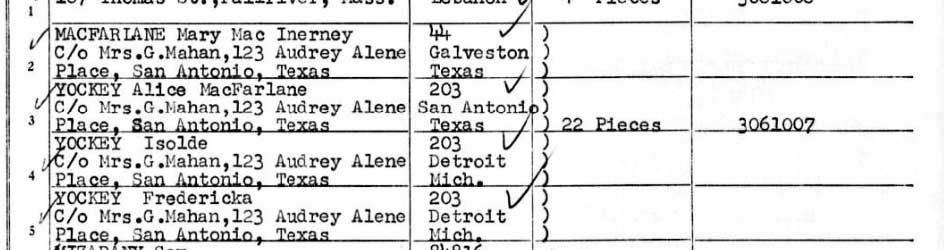

Fredericka’s birth name was Carlotta Fredericka Yockey, but supposedly her father nicknamed her Brünnhilde or Brunhilde. [4] If she’s calling herself that in Texas in 1957, this suggests to me a deep and abiding bond between FPY and his daughters. We know he spent time in the Mideast in the 1950s, and surreptitiously he must have visited the kids.

Fredericka’s birth name was Carlotta Fredericka Yockey, but supposedly her father nicknamed her Brünnhilde or Brunhilde. [4] If she’s calling herself that in Texas in 1957, this suggests to me a deep and abiding bond between FPY and his daughters. We know he spent time in the Mideast in the 1950s, and surreptitiously he must have visited the kids.