This was supposed to be a year-end book roundup, but I had a difficult end of year. So for the present I’ll pretend this is the 53rd or 54th week of 2023 (a nasty year altogether).

When my husband died a few weeks ago, I found a number of “overdue” library books in all manner of places. I stacked them by the door. That’s pretty much how we did things here. He’d take out a lot of books and then, when he saw me making an exit, he’d go, “Oh, if you’re going out, could you take those back to the library?” He’d say that even if I was just going out to the trash bay. Some months back The New York Public Library stopped charging fines when you didn’t return a book on time. Thus “overdue” became a mere figure of speech. I don’t think this has worked out well for the NYPL. They recently stopped Sunday operations because they were running out of money.

Like newspapers when you’re painting the walls, books on the floor acquire a special appeal they lack on the shelf. I found that two of the big ones here were immensely readable. Slouching Towards Utopia [1], a great thwacking doorstop of an economic history (180,000 words, supposedly, plus index and apparatus) can be opened at any random page and found lucid and enjoyable. It’s very much a big-think book, as author Brad DeLong wants to sell us his Grand Unifying Theory. However, this Cal Berkeley professor has been writing this theory and its related components for about thirty years now (and blogging it for most of that time, first on his own website, then on Typepad, now on Substack), so he’s capable of being both engaging and abstruse at the same time.

I haven’t exactly read this book. I have dipped into it, and I have read about it, mainly through book reviews that are mostly similar (no doubt because they’re recapitulating the flyleaf blurb and the publisher’s press release). But I’ve seen enough of it to form an opinion, and that is that DeLong’s Great Unifying Theory is fun but ramshackle. Sort of like Toynbee. He believes we recently ended a very long era of economic growth, and we are not yet acclimated to the new crises that face us. As related by a reviewer in The Atlantic at the time of publication 16 months ago:

[DeLong] decided that the era that had begun in 1870 ended in 2010, shortly after productivity growth and GDP growth had collapsed, as inequality was strangling economic vibrancy around the world and revanchist political populism was on the rise.

“Inequality [is] strangling economic vibrancy.” “Revanchist political populism.” You see where this is going. DeLong is a progressive, an economic liberal, the sort of person who derides motives of an idealistic, transcendent, nationalistic nature. Our best interests cannot possibly involve cultural and racial preservation, or morality: we must bow down instead to peace and productivity, to materialistic growth and gain.

We’re used to such tendentious arguments from quasi-libertarian outfits like American Enterprise Institute and the Cato Institute, and from public-policy anarcho-libertarians such as Jeffrey Tucker. As a philosophy it’s just the sterile butt-end of the Whig School of History. The best that can be said for it is that it has proven itself unworkable and, as DeLong admits, has collapsed. And it’s collapsed because of its inherent contradictions. “Revanchist political populism” is in the ascendant because, in the end, people and nations will do what they have to, in order to survive.

Another “overdue” book I must take back to the library is Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes, by Tariq Ali [2]. Tariq Ali has one job in this world, and that is to be furious and contrarian. Winston Churchill is a perfect target. My husband used to love to watch Tariq’s many YouTube videos, simply for their entertainment value. The one I just linked pertains to this biography (one might cheerfully say “hatchet job”) of Churchill.

Tariq’s Leftist twitch is often annoying—it all seems to derive from being an aggrieved Asiatic in Britain who thinks he’s under-appreciated as an intellectual because he’s an ancient Paki—but it works very well in this instance. He throws everything he can think of at old Winnie. How Churchill crushed the Jewish revolutionaries in Sidney Street in 1910; how he sent armed cavalry against the Welsh coal miners in Tonypandy in 1911; and of course, the stories about the Black and Tans in early-20s Ireland, and the suppression of the General Strike in 1926; as well as minor sidelights such as his mockery of the Bengal Famine in 1943 (“Then why isn’t Gandhi dead?”). So on, so forth. I wonder whether the author considered that many readers who didn’t like Churchill before, will now begin to have warm and fuzzy thoughts about him.

Tariq delights in Churchill quotations that might be called “racist,” and adorns the back cover with them, e.g.,

I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly-wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.

Not bad, eh? We even get the 1964 Gerald Scarfe caricature of WAC on his last day in the House, shown above. (Drawn for The Times, which wouldn’t run it, thus given to Richard Ingrams at Private Eye, who did.)

Only rarely does the author bore us with rote Marxian nonsense such as Fascism being an end-of-life stage of Capitalism. That formulation puts me in mind of Scott Fitzgerald’s musing that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” (From “The Crack-Up,” Esquire, 1936.) I suppose Tariq Ali passes that test. But, really, must he?

Traitor King [3], about the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, is not as scurrilous and scandalous as it might have been. That would have required Andrew Lownie to surpass Andrew Morton’s 17 Carnations (2015), a book which took its name from one of the many smears against the Duchess, alleging that she had sexual relations with Joachim von Ribbentrop seventeen times, after which Ribbentrop sent her 17 carnations every day.

There are many things wrong with Lownie’s Traitor King, but lack of research diligence and fluency are not among them. Andrew Lownie is a one-man book factory. He’s a successful literary agent and author and appears to do his own legwork. What he is not is a fact-checker, or discriminating judge of dubious stories. He is thus prone to errors small and large. At one point he describes a March 1941 directive from the British Embassy in Washington, that the Windsors not visit Puerto Rico, “where its president, Rafael Trujillo, is thought to have important Nazi connections.” At this time the Duke of Windsor was governor of the Bahamas and kept under close scrutiny.

This directive seems to be typical of British diplomatic and intelligence communiqués of the time. It’s factually wrong, hilariously wrong. Trujillo was the Dominican Republic’s strongman, while Puerto Rico was a U.S. territory and did not have a president. But more importantly there’s the deliberate innuendo that the Windsors are sneaking off from their exile in the Bahamas to break bread with their Nazi friends. The factual basis here seems to be that Mrs. William Leahy, wife of the ambassador to Vichy, France—Admiral Leahy had recently been governor of Puerto Rico—heard a report that the Duchess, Wallis Windsor, had visited San Juan. This story found its way to the U.S. consul in the Bahamas, who told the State Department in Washington, who told the British legation, for whom it was just catnip.

The story of the Windsors in the Bahamas is just littered with innuendo of this sort. Earlier in that winter of 1941, Alfred P. Sloan, head of General Motors, visited the Bahamas with his colleague James D. Mooney, president of General Motors Overseas Corporation. There’s no evidence at all that this wintertime sojourn to the islands was a rendezvous with Nazi industrialists or even a skull session with the Governor of the Bahamas. Yet that is how diplomatic channels were eager to portray it. George Messersmith, a somewhat unhinged American diplomat who had been keeping tabs on the Duke (officially and otherwise) ever since the Abdication, now filed a State Department report describing GM’s Mooney “as mad as any Nazi” and one who hopes to become “our Quisling or Laval” when “the United States may turn fascist.” Above all, there was constant suspicion and surveillance of Axel Wenner-Gren, the Swedish Electrolux tycoon. Wenner-Gren owned Hog Island (present-day Paradise Island) near Nassau, where he built an estate that gave employment to 15% of the black Bahamian population. Through his far-flung contacts in government and industry, Wenner-Gren had been lobbying to end the war through a negotiated peace. But for the War Party in Britain, and their American sympathizers, “negotiated peace” was code for “appeasement” and “letting the Nazis keep what they’ve won.” But there’s no evidence that Wenner-Gren was ever anything more than a philanthropic tycoon, with a proud legacy and ongoing foundation.

The smears against the Windsors, Wenner-Gren, and Sloan, Mooney and GM, all have the earmarks of a coordinated black-ops campaign. I have no doubt that much of this campaign was helmed by William “Intrepid” Stephenson, who was already running his British Security Coordination spy-and-disinformation agency out of the International Building in Rockefeller Center. But there were also people like Messersmith, who would join in the fun for free, just for the sport of it. (Messersmith had been doing similar numbers on Joseph P. Kennedy the previous year, when Kennedy was ambassador to England.)

It’s not clear whether Lownie himself is simply gullible when reproducing this dubious material. Perhaps he’s just making a sound business decision. (Did the editors of News of the World sweat and swinge over their headlines?) His treatment of the Marburg Files simply burnishes the account shown in The Crown: there were German Foreign Ministry papers, there were documents signed by Ribbentrop, there were communications relating to the Duke of Windsor in the Phony War period, and during the Windsors’ initial flight to Spain and Portugal before their Bahamian exile. But, in a word, the Marburg Files are chickenfeed. The drama surrounding them is the real story. And much of that is undoubtedly fiction. We are expected to believe that an American officer named David Silberberg, a German-born Jew, just happened to be strolling through the Harz Mountains when he came across an abandoned vehicle with German Foreign Ministry papers scattered over it. That is the story Silberberg told. And this supposedly prompted him to visit local castles, on the off-chance that there were more papers. And what do you know—there were! An “almost complete archive” of the Ministry, in fact! Quelle coincidence!

Lack of discernment does not seem to have been the problem with the most ludicrous bits Lownie throws into the book. He has long, purple, thumbsucking passages where he discusses whether or not the Duke was “gay.” Twice he quotes lurid postings from the online homosexual gossip forum Datalounge (see Chapter 19). Lownie doesn’t mind that it’s scurrilous; he puts it in because it’s scurrilous. And sells books, I guess.

And then we have Scotty Bowers of Full Service fame, the gas-station jockey who for 50 years was supposedly Hollywood’s favorite pimp. From his own first-hand experience, Scotty assures us that “Eddy” (the Duke) was a whiz at fellatio.

If I object too strenuously to the foregoing nonsense, I’ll look like a bluenose who can’t enjoy the joke. Yes, I get it—it’s all in fun. But here’s a bad joke I can’t enjoy: the title of the damn book. “Traitor King” is an oxymoron. Treason, at its core, is betrayal of your king, and giving aid and assistance to the king’s enemies. Whatever you may think of King Edward VIII, afterwards Duke of Windsor, he did not betray himself or give assistance to his enemies. Others may have switched sides and tergiversated, but this gentleman forever walked a straight line.

Hollywood: The Oral History [4] is a mixed bag. It follows the basic template created forty years ago by Jean Stein’s oral bio of Edie Sedgwick. But while that worked very well for Edie, wherein the subject lived just a short while, and the memories were mainly from the 1960s, here we have recollections from many more people, and they stretch through most of the 20th century. They are taken from talks and interviews beginning in 1969 at the American Film Institute. I don’t think of 1969 as being that long ago (I mean, that was Woodstock, maaan), yet I find it somewhat astonishing to think that most of the big-name directors and stars of the Golden Era—even those of the Silent Era—were still very much alive in 1969 and even into the 1980s.

We have the unsinkable Lillian Gish (1893-1993) telling us how in the early days Hollywood was a great place for women to get ahead because there were so many opportunities. “I got to direct a film when I was twenty. With my sister Dorothy.” Well that would have been 1913, and with D. W. Griffith standing nearby I can’t imagine the technical challenges were particularly onerous.

The book suffers from a superfluity of empty encomiums, with far too many cinema veterans gushing at us, “Oh that Mister Mayer, he was such a doll! MGM was such a great place to work! More stars than there were in Heaven!” I much prefer the sourpusses, such as the director John Cromwell (father of actor James) who has a great story about Darryl F. Zanuck taking no prisoners:

In talking about a story point in conference one day, he [Zanuck] talked about a millstone when he met milestone. The writer, new to the studio, used the correct word later rather emphatically. After the writer left, Darryl turned to the producer, and said, “Where did that guy come from?” Upon receiving the answer, he said, “Fire him.”

Cromwell was not a member of the L. B. Mayer fan club:

I met Mr. Mayer, of course and found him to be the type of man I could not admire. To me he was domineering, ruthless and humorless…

This is immediately followed by Pandro S. Berman, who must have been a real brown-noser:

Right. Oh, Louis Mayer was a great man. There’s no question about it. He was not necessarily a nice man, and a lot of people had a lot against him. But he was a great man in his job.

And now here’s Pandro Berman on RKO founder/conglomerateur Joseph P. Kennedy:

I worked for RKO for so many years… I remember many times when I was in contact with old man Joseph P. Kennedy during his operation of the company when he would come out here for a few months at a time or a few weeks. In fact, I once talked him into giving me a $5 raise when I couldn’t get it from anybody else in the organization… He was a nice man, Joseph P. Kennedy. I liked him. He had the studio filled with Bostonians…

What’s missing from the book, because it was missing from the AFI lectures, is input from the gearheads and wirepullers who made the train run. We know movie theaters went from silents to talkies in the space of about one year, 1928-29, but the technical details are left a mystery. When Al Jolson briefly sang in The Jazz Singer in 1927, the noise was coming from a gramophone record, synchronized and amplified (if all went well). Talkies took over not because of this clumsy novelty but because of an RCA optical-sound technology that printed a code near the edge of the film strip, which could then be read and broadcast by a new series of projector. This basic technology remained standard for the next forty years. Mr. Kennedy bought up about 800 vaudeville-circuit houses, wired them for the new RCA/RKO sound system, and by 1929 rival studios and chains had to follow suit. How many other technical innovations do we take for granted or put down to discreet natural evolution?

The London Review of Books assigned this book to John Lahr to review. It was so difficult for him to get a handle on, that Lahr spent the first 2000 words telling about how he sold his first novel (The Autograph Hound) to Hollywood 50-odd years ago, and was glad-handed by everyone, especially by his showhorse director Sydney Pollack. He even let them change the story so it was set in Los Angeles (much cheaper) rather than New York. Then a studio head decided the movie wasn’t to get any international sales, and the project was axed. Lahr thereupon flew back to London, back to subsisting on pin money from reviews and essays. I think he’s stayed there ever since. John Lahr had been born in L.A. but he was not of L.A. He left as a babe when his father Bert found there would be no more Cowardly Lion roles, and took the family back to New York, where Broadway always beckoned.

The prolific Sam Wasson is co-curator of these reminiscences. He wrote one of the best Hollywood histories ever, The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood, which tied together the unbelievably intertwined stories of the lives, misfortunes, and drug frenzies of screenwriter Robert Towne, his wife Julie Payne (son of John), Robert Evans, Jack Nicholson, his girlfriend Anjelica Huston, and finally Roman Polanski—whose 1977 arrest for sex-play with a 13-year-old in Jack Nicholson’s Jacuzzi came about ultimately because cops came to the house later and found drugs in Anjelica’s handbag. It’s complicated. Wasson’s latest book is a biography of Francis Ford Coppola, probably my next read.

The Washington War [5]. Excellent. A not particularly fetching title for a book, and even less attractive when you find out it looks like another rehash of office politics during the Second World War. This is done in the same revisionist vein as Nigel Hamilton’s three-volume enshrinement of Franklin Delano Roosevelt a few years back. Hamilton made Churchill look like a complete ass, forever proposing to squander men and matériel on daffy, far-flung raids and invasions in the eastern Mediterranean and up through the valleys and mountains of Slovenia. Churchill, like Alan Brooke and most of the British high command, was thoroughly fearful and defeatist about making a cross-Channel landing in France. This is how traumatized the British command still was, in 1942-44, over the events of May 1940.

Author James Lacey, an instructor at the Marine Corps War College, takes Hamilton’s theme even farther, making Churchill not only a time-wasting ditherer, but a deceitful incompetent, forever agreeing to a strategy with FDR, then immediately trying to wheedle his way out of it when the plan is to be put in motion. Lacey’s account is equally devastating with regard to George Marshall, the most inept and overpraised “Architect of Victory” in history. From America’s entry into the War, Marshall was all for leading an immediate crusade into Normandy, even though as Army Chief of Staff he knew he had no army to speak of, and would need at least 20 divisions to begin to imagine a D-Day assault. Another inept, more sinister character in the cast is Henry Morgenthau, who seriously, deeply, wanted to pastoralize Germany and starve 40 million Germans to death, never mind what the knock-on effects would be for the rest of Europe. The Morgenthau Plan was not of his own making (Harry Dexter White, the Red-tinged Lithuanian Jew, was the actual author), but Morgenthau backed it, and pressed it upon a failing Roosevelt who was often non compos mentis and later had no recollection of ever signing off on it.

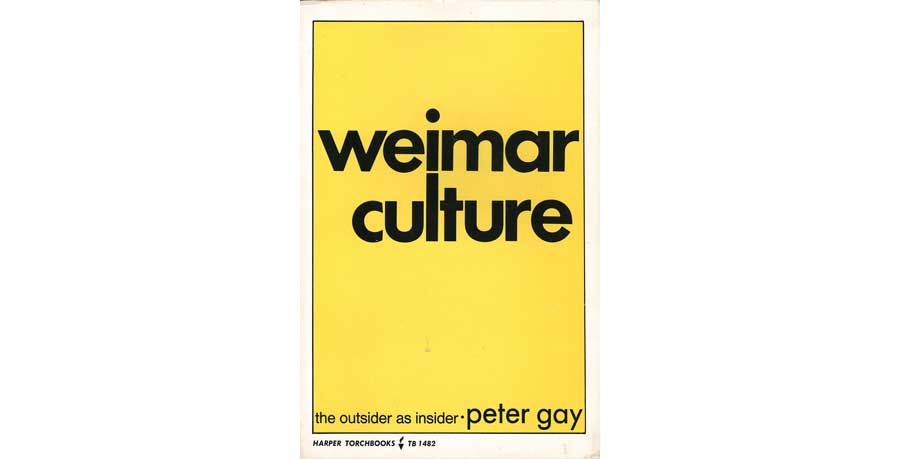

Somewhere between Thanksgiving and Christmas I was tempted to search for a book I’d once had to read for a Henry Ashby Turner history course, Weimar Culture [6]. Editions abound, but there are very few copies available of the paperback version I had. This is important, because its cover design is the only one that actually shouts its title. It’s in Paul Renner’s 1927 Futura font, as Bauhaus as you can get. The font was ubiquitous in the later Weimar years, and was also popular throughout the Nazi period and for decades afterwards:

What prompted my search was some whiner on social media saying, “Nobody knows anything about Weimar Germany! Nobody teaches it!” Which is nonsense, because many of us got it up the wazoo. So on eBay I found this near-mint paperback edition, identical to the one I had in college. I eagerly addressed it, curious to know if it was eye-glazingly dull and impenetrable as it seemed the first time around. And you know what? It was! It is!

I remember learning exactly one thing from it, back in the day: the word cartelization. It means making a monopoly, or trust, of similar businesses, so they don’t waste money and effort competing with each other. Everything else worth knowing—Bauhaus architecture, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari—you can easily pick up elsewhere. Trying to toss everything from 1919-1932 Germany into a big pot and making of a meal of it, is a hopeless enterprise. So the book is still dense and impenetrable, each page littered with a dozen obscure names venturing an obscure opinion. Any one of the chapters could probably be expanded into a PhD dissertation, and indeed, that is what the book might be best considered, a bibliographic source.

Peter Gay’s original name was Peter Joachim Frölich, and he was a very un-Jewish-looking Jew from Berlin, born 1923. He and his parents were booked to sail on the St. Louis to Havana in 1939, but then discovered a ship that was sailing two weeks earlier, and took that instead. At college in Colorado he changed his name to Peter Jack Gay. Then he went to Columbia for graduate school. My mother had recently transferred from Penn to the School of General Studies (Columbia’s non-collegiate college), and somehow she and her brother got to know Peter, though I could never get precise details.

“Oh we knew Peter Gay. He was over at our apartment many times,” my mother would say in her blasé way, when she saw me with a copy of Weimar Culture.

“But what did he do? What did he say?” I insisted.

“Oh he was a guest in our house many times,” my mother would say again, in her impenetrable way.

Notes

[1] J. Bradford DeLong, Slouching Towards Utopia. New York: Basic Books. 2022. [2] Tariq Ali, Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes. London and New York: Verso. 2022. [3) Andrew Lownie, Traitor King: The Scandalous Exile of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. London: Blink Publishing. 2021. Also: New York: Pegasus Books. 2022. Lownie himself does a very good spoken-word version available on Audible. There are some slight differences in the various editions. E.g., the mixup about Rafael Trujillo was excised in the American edition, along with other obvious errors. These corrections may well be what are meant by the “Fully updated with new research” on the British paperback edition displayed. [4] Jeanine Basinger and Sam Wasson, Hollywood: The Oral History. New York: Harper. 2022. [5] James Lacey, The Washington War: FDR’s Inner Circle and the Politics of Power that Won World War II. New York: Bantam. 2019. [6] Peter Gay, Weimar Culture. New York: Harper Torchbooks. 1970 (this edition).