Edward H. Miller

A Conspiratorial Life:

Robert Welch, the John Birch Society, and the

Revolution of American Conservatism

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021

Margot Metroland

A writer friend of mine, now long ensconced in the Condé Nast glossies, used to regale us with his mother’s nutty ideas on matters of politics and society. For example, when the kids were young and at the Safeway in Palo Alto, mom would loudly refuse to buy Welch’s grape juice or jelly—even the grape jelly that came in Flintstones glasses—because that would be giving money to the John Birch Society.

If memory serves, this mom was a nurse. In my experience, nurses tend to be gullible and incurious. (No special aspersion on the nursing profession; much the same can be said of schoolteachers.) So I imagined this was just some scuttlebutt she’d overheard one day at the nurses’ station. Mom never bothered to research the matter herself, or she would have discovered that there was absolutely no connection between John Birch Society founder Robert Welch and the grape juice people. That Mr. Welch, and his brother James, were actually candy tycoons. The James O. Welch company made Junior Mints and Pom-Poms and Sugar Babies. The sort of stuff you found mostly in movie theaters, or at the bottom of your Halloween sack when all the Hershey bars and Milky Ways were gone. I would guess my friend and his siblings ironically ate their share of this geedunk growing up, even while being denied the sublime pleasure of collecting Flintstones jelly glasses.

The author of A Conspiratorial Life is guilty of the same wide-eyed naivete and goofy commonplaces as my friend’s mother. His basic thesis, iterated over and over, is that a) modern conservatism is fueled by Conspiracy Theories and Conspiratorial thinking; and b) it all began with Robert Welch and the John Birch Society. And not just conservatives as we generally understand them. Donald Trump gets pulled into this lazy, facile argument as well, with author Miller accusing Trump of all sorts of false claims and imaginary outrages that Miller imagines are in the tradition of Welch and the Birchers. There may be a parallel between Donald Trump and Robert Welch, but it lies mainly in the exaggerations and pure inventions thrown at them by the Leftist press and broadcast media.[1]

The facile comparison to Donald Trump is put there because without it, the book has no “hook.” It’s not 1964 anymore. Robert Welch and the Birch movement are so far off most people’s radar, no book on Birchers is going to get attention unless you stuff it full of sensationalism and Trump. (A 2022 book, Birchers: How the John Birch Society Radicalized the American Right, by Matthew Dallek, offers a more focused and detailed history of the JBS and conservatism since the early 1960s. Yet even here, the book’s dust-jacket blurb is obliged to begin with: “Long before Donald Trump and QAnon spread far-right conspiracy theories, there was the John Birch Society.”)

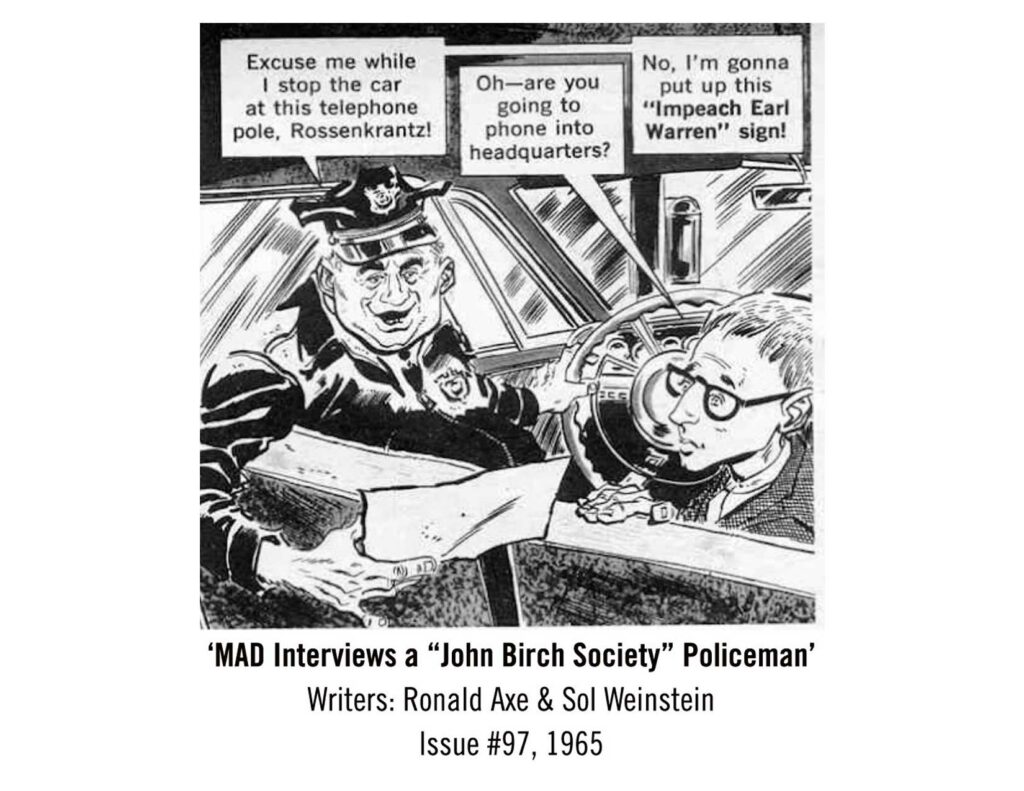

More than anything else, Miller’s take on the Birchers reminded me of a strange piece that appeared in Mad magazine in mid-1965, in which somebody “interviews a John Birch Society policeman.” All the media clichés are here. The Birchers insist their aim is to fight Communism, yet fundamentally they’re sloganeering hoodlums who use that as a pretext for displaying racial prejudice, xenophobia, suspicion of Jews. And of course they want to “Get US out of the UN,” and impeach Chief Justice Earl Warren (not because of his Commission’s fake “investigation” of the Kennedy assassination, but because of that Brown v. Board of Education decision back in 1954).

A running joke in the Mad story has the thuggish cop repeatedly wondering what the interviewer’s last name, Ross, is short for. He keeps calling him “Rossenkrantz,” “Rossiwicz,” “Rossokovski.” The guy works for Mad, after all! [2]

This is about the level of analysis we get in A Conspiratorial Life. Author Edward H. Miller, an “associate teaching professor at Northeastern University,” isn’t particularly interested in presenting tenure-track history about what motivated Robert Welch and the Birchers. He mainly wants to tell us how they appeared in pop culture. The result is the sort of thing you come up with when your basic modus operandi is doing internet searches for incendiary opinion pieces. Which is perfectly okay with me, so long as no one mistakes this casual journalism as serious research.

Still, we end up with a presentation is often too naive by half. When I saw that Miller was trying to claim that “conspiracy theories” in politics began with Robert Welch and the JBS, I immediately went to the index to see if Miller had ever heard of Richard Hofstadter. Hofstadter was a Columbia history professor who famously published an essay in Harper’s called “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Robert Welch and the Birch Society are not mentioned in this November 1964 piece because they are not the main target of the essay. That would be Senator and Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater (also not named) who was at the time being smeared “mentally ill” and “paranoid” in other publications.[3] But Hofstadter didn’t have to mention anyone by name. in the fall 1964 he and the Harper’s editors had merely to mention paranoid politics to put across the innuendo that Goldwater and his supporters (Bircher-types, notably) were suffering from a mental malaise, a pathology that Hofstadter claimed was recurrent in American political history. Hofstadter took his “conspiracy” thesis all the way back to the 1700s: to theories about the Illuminati, and then fear of Freemasonry, the Jesuits, the Holy See, the Habsburgs, and finally the subversive networks of the Abolitionists. Often shallow and frivolous, the essay doesn’t directly discuss contemporary 1960s politics. Regardless, Hofstadter confutes Miller’s pinwheel notion that Conspiracy Politics were something new in the early 1960s, sprung from the loins of the John Birch Society.

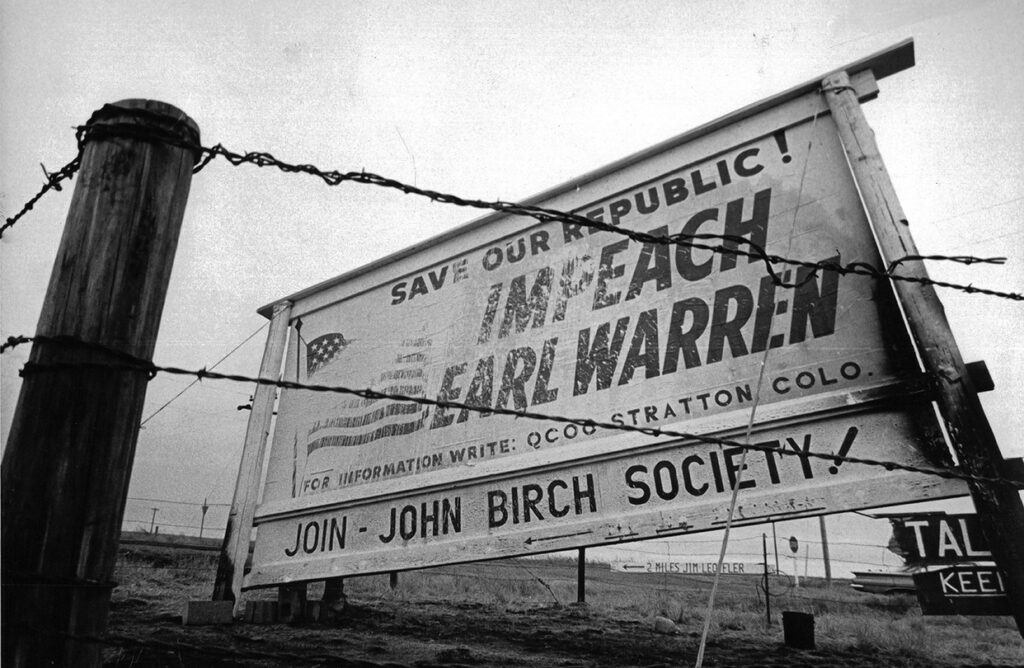

On the other hand, true facts are often dull. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” As I say, it’s the cockeyed legend of the John Birch Society that Miller is really after. Sixty years ago the JBS was commonly portrayed in the media as a shadowy group of “extremists.” “Extremism” in fact became a sort of journalistic synonym for Bircherism. When Barry Goldwater gave his acceptance speech at the 1964 Republican Convention and said, “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” this was widely understood as giving the high-sign to the John Birch Society. In racial matters Birchers were mostly pro-segregation, or at least anti-integration, and they opposed the rash of Civil Rights legislation. And they put up “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards.

Birchers were said to be a lot else besides quirky and extreme. From the beginning there was believed to be an undercurrent of anti-Jewish policy in the Bircher movement. Welch was very chary of this rumor, because he knew it was a smear used against any nationalist movement, going back at least to the America First Committee of the early 1940s, to which Welch belonged. In the early 1960s Time magazine and even President Kennedy suggested that Welch’s movement was somehow akin to Hitler’s. (Who planted that suggestion, one wonders?) Nevertheless you’d be very hard put to find any suggestion of anti-Jewish or pro-Nazi remarks in the lengthy, soporific essays published in American Opinion. Welch was so nervous on the subject he insisted his editorial staff vet any article written by Revilo Oliver or Westbook Pegler, the two likeliest offenders.

This chariness about the JQ and other sensitive matters is what led to the eventual falling out between Oliver and Welch. In A Conspiratorial Life, Miller claims that Welch “fired” Prof. Oliver. This is based on the sanitized memoranda that Robert Welch left behind, and to which Miller had access. But Revilo Oliver told a very different tale, denouncing Welch as a hypocrite, liar and coward.

Birch geopolitical analysis seemed obscurantist, like nothing you’d read in Foreign Affairs or the New York Times. It was dense, often quirky, reinventing usual assumptions about international relations. For many years the magazine, American Opinion, published an annual “Scoreboard Map” of the world, showing what percentage of “Insider” subversion each country had thus far succumbed to. It was hard to say what criteria were being used here. The USSR and Red China were of course 100% enslaved, but then you had Western European countries with quasi-socialist economies, and they seemed to be halfway there. The International Communist Conspiracy seemed to be mainly an juggernaut aimed at economic freedom.

In this respect, JBS ideology of 50 or 60 years ago was very similar to what you’d find with militant Libertarians. Questions of race, religion, ethnicity, in-group preference and social cohesion were off the table as debate issues, as they were seen as distracting and anti-individualist. Birch writings would discuss such matters only in the most roundabout way, as when Citizens’ Councils spokesman Medford Evans (father of M. Stanton Evans) would write about Communist control of the Civil Rights movement. The Big Conspiracy was really a war against the individual and in favor of group-think and collectivism.

Libertarianism and Bircherism had much in common, but like most commentators Miller misses that completely. The main reason for their similarity, I submit, is that their ideology provided a protective “duckblind” for anti-liberal political agenda. You were against integration and the Civil Rights movement not because you were a prejudiced bigot, or you were a race-realist bore with degrees in anthropology, but because you opposed intrusive Federal legislation and believed in freedom of association, yada yada. Such talking points were very useful for someone selling JBS or Libertarian agenda to wishy-washy Republicans. It’s no accident that notable conservatives such as Phyllis Schlafly, Barry Goldwater, and Ronald Reagan were friendly to both camps.

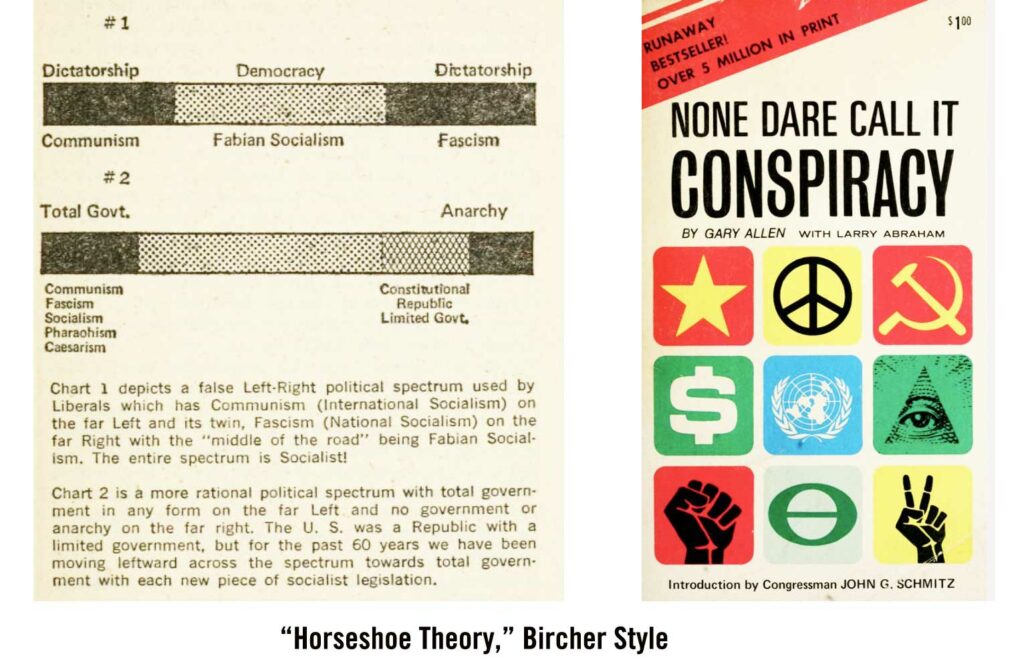

The Libertarian-Bircher overlap was illustrated succinctly in a Birch paperback called None Dare Call It Conspiracy. Prepared for mass-distribution during the 1972 Presidential campaign, it carries a foreword by American Independent Party candidate John Schmitz. In less than 100 pages None Dare Call It Conspiracy offers a political primer touching on every conspiracy cliché you’ve ever heard, and some you haven’t (with the notable exception of The Protocols of Zion [4]). You get the Illuminati, the Council of Foreign Relations, the Trilateral Commission, the Bilderbergers, Cecil Rhodes, Colonel House, Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, and that esteemed Georgetown professor Carroll Quigley, who spilled the beans on the Conspiracy “Insiders” in his monumental doorstop, Tragedy and Hope.

You also get a clear explanation of how you’ve been lied to all these years, with political models that pretend Fascism and Communism are opposites, at outer extremes of the political spectrum. None Dare Call It Conspiracy sets the record straight, demonstrating that both types of dictatorships are really collectivist and socialist! Real extreme right-wingers are actually anarchists! How’s about that? Look, we have charts here and everything…

The top bar chart is of course a rendition of the “horseshoe theory” of politics, which claims that political extremes are really very similar. “They meet at the ends,” as the saying goes. The second chart is how Libertarians and Birchers prefer to see the world. Or at least did, in the early 1970s. There was a great of cross-fertilization among Rightist theorists in the 1960s. Barry Goldwater’s speechwriter and adviser Karl Hess eventually evolved into a Libertarian near the anarchist range.

It’s not clear why the JBS did not take on a clear Libertarian identity as time went on. Undoubtedly some Birchers did redefine themselves that way, taking on the protective coloration of the American Enterprise Institute, the Mises Insitute, the American Institute for Economic Research, and other outfits that present themselves as free-enterprise think tanks that don’t mess around with such touchy subjects as culture, race, nation.

Another aspect of the Robert Welch/JBS story that author Miller avoids is how and why Welch was at once a brilliant organizer yet a stubborn crank who was forever painting himself into a corner. Welch was a genius, undoubtedly; taught himself to read at 2 or 3, graduated from college at 16, then on to the United States Naval Academy and Harvard Law School, often supporting himself along the way by tutoring other students in mathematics and languages, in both of which he had great facility.

My impression is that, having been a child prodigy, and being measurably brighter than nearly everyone else he ever met, Welch became a confirmed autodidact, untrusting of anyone’s opinion unless it conformed with Welch’s own. Most people were gullible, Welch could see that clearly; through his life he remained suspicious of popular beliefs and consensus opinion. If Welch did not discover a useful fact or come to a conclusion on his own, that information was probably wrong, or not worth knowing. This would be the case even if the argument came from another prodigious mind, such as Revilo Oliver’s.

With his personality and gifts, Robert Welch was doomed always to be at odds with the world; impetuous, obstinate, impatient. He sailed through Annapolis and Harvard Law—but then dropped out before graduating. He started a candy business because he could run it on his own, and was certain he could do better than anyone else. Self-assured and innovative, he invested too much too soon in expensive equipment just as the Depression came into sight. And then he went bankrupt, and was forced to go to work for his younger brother…selling Sugar Daddys and Pom-Poms for the next 25 years, for the James O. Welch candy company of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Notes

[1] The book’s Introduction begins with a nice summary of the book’s confused thesis. Supposedly Donald Trump called for the death penalty for the 1989 “Central Park 5” gang-rapists, even after the five Urban Youth of Color were all exonerated by DNA testing. (Except of course they weren’t exonerated by their DNA, nor were their convictions based on DNA.) Author Miller says Trump propounded a “baseless” claim that Obama was born in Africa. (He didn’t.) He claims Trump said all Mexican immigrants were rapists and drug runners. (No.) And that Trump threatened to jail Hillary Clinton in 2016 for her illegal e-mail server. (Not quite . . . but you get the picture.) None of these resemble claims made by or against the John Birch Society. [2] A very odd piece for Mad in those days, as the magazine generally specialized in lighthearted absurdity, not mean-tempered political smears. I did not recognize the writers of the piece, Ronald Axe and Sol Weinstein, as regular Mad contributors, so darkly suspected that the article had been an ADL plant, perhaps as some trade-off to help the publisher, Bill Gaines, get wider circulation at newsstands. Whatever the true story behind it, Axe mainly wrote TV sitcoms (Get Smart, The Mothers-in-Law), while Weinstein did spy spoofs for Playboy about a Jewish James Bond. Meanwhile the artist selected to illustrate the comic strip was none other than Joe Orlando, of EC Comics, Classics Illustrated, and the long-running comic-book ads for Harold von Braunhut’s brine-shrimp “Sea Monkeys.” Usually a very precise draftsman, Orlando turned out the four pages of “JBS Policeman” in an unusually loose, slapdash manner. Was he drawing badly on purpose? [3] Ralph Ginzburg’s Fact magazine was successfully sued for running a 1964 cover article asserting that over a thousand psychiatrists regarded Goldwater and mentally ill and unfit for office. [4] The Anti-Defamation League kept mum about the book, and the American Independent Party, until after the November 1972 election. Then the ADL put out the word that John Schmitz and None Dare Call It Conspiracy were part of a new wave of Jew hatred: “The book is saturated with anti-semitism of the kind disseminated by anti-Jewish propagandists for more than 50 years,” said a spokesman, quoted in the New York Times (November 20, 1972). There was nothing at all in the book about Jews, nor had there been anything like that in the Schmitz campaign.